Frank McEwen

Born: April 19, 1907

Died: January 15, 1994

Written for the Catalog of the opening of the Rhodes National Gallery by Frank McEwen Salisbury, Rhodesia, July, 1957

“Triumph of First Congress on African Culture” London Times, 1962

“The Dark Gift” Time Magazine, Sept. 28, 1962

A trip to Africa: Frank McEwen, Rhodesia and Shona Art, 1968 by Adele Aldridge

Obituary: The London Times – January 17, 1994

“Frank McEwen,OBE, Artist ,teacher, administrator, and the founding Director of the National Gallery of Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) died in Illfracombe, Devon, on January 15, aged 86. He was born on April 19th, 1907.”

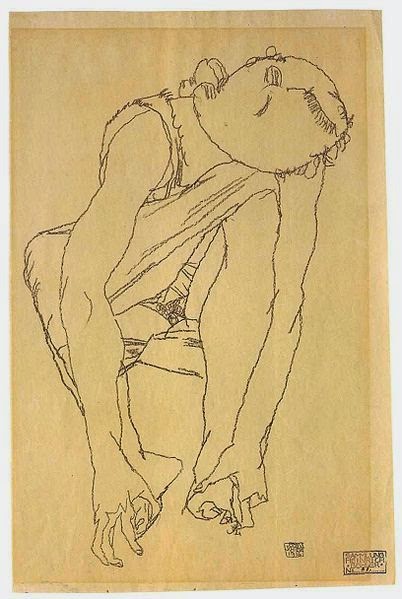

Francis Jack McEwen grew up with a collection of West African art, much of it high quality, which his father had picked up as curios in the course of business trips there. He went to Paris in 1926 to study art history at the Sorbonne and the Institut d’Art et d’Archaeologie under Henri Focillon, who was a pioneer in the study of so called “primitive” art. Focillon was much admired by living artists and this led McEwen to friendships with Brancusi, Braque, Matisse, Picasso and Leger. He also absorbed the great respect of these artists for the teachings of Gustave Moreau, who had died in 1898 , and who believed in drawing out of people an art which was individual to themselves.

Focillon advised McEwen, with these interests, to be a man of action in art, rather than a lecturer. McEwen decided to be a painter, quarreled with his family, was left with out a sou, and set out on his wander years, working his way around the museums of Europe by menial work at power stations. He spent most of 1928-1929 working in Flanders, and painting in his spare time – wild flowers were his specialty, since they sold quite well: he exhibited back in London at the Goupil Salon and the New English Art Club.

Photo: Mary and Frank McEwen

After this good start for Anglo-French relations, London inflicted a show of modern British artists which was a dismal failure. Then McEwen’s introduction of Henry Moore, who had been over to Paris to stay with him three times, to Picasso, Braque, Brancusi, and the leading French critics and museum administrator, led to the show of Henry Moore in Paris at the end of 1945.

Shows of Turner (McEwen had helped put Turner watercolors between sheets of blotting paper at the Tate after the flooding of 1927) Blake, Sutherland and Chadwick followed. McEwen’s belief that the way to support British art in Paris was to show French art simultaneously in London, worked well: Picasso and Matisse were shown at the Victoria and Albert Museum in 1945, Braque and Rouault in 1946 and Leger and Dufy in 1947. (The hundreds of letters of protest to The Times about the Picasso show caused much merriment to Picasso when McEwen translated them to him.)

Around 1952, McEwen felt that the School of Paris was getting trivial in its content. He had been taking more interest in African culture, and when the idea of founding the Rhodes National Gallery in Salisbury, Rhodesia, was formed, McEwen was consulted. He went out to Rhodesia for a month in 1954 for consultation. He found no art going on there, black or white, to impress him: and anyway, the intention of the museum’s board was to stock it with European old masters. African art was not to be considered.

McEwen’s past experience suggested to him that a gallery would only thrive on exchanges of art – that there had to be some sort of local art going on. When a director was subsequently sought – before the building of the gallery – McEwen applied, encouraged by Picasso and Herbert Read, and to his surprise was selected. He asked for a year’s grace, resigned from the British Council, and sailed his beloved boat from Paris down the Seine to Mozambique via Brazil and round the Cape.

Sitting on the low foundations of the future National Gallery as it was being built, McEwen met Thomas Mukarobgwa, who talked to him about the Shona tribe, their religion, their dance, and their music. Since the authorities insisted that all the staff of the gallery be ex-policemen, McEwen got Mukarobgwa in as a cleaner, and gave him, and his friends who followed him, drawing and painting materials. Thus an unofficial workshop was formed in the basement. After about a year, the vigorous “Afro-expressionism” of the paintings was spontaneously superseded by carving in local stone – from soft soapstone to hard serpentine and verdite.

Joram Mariga was one of the first to attempt this and McEwen encouraged him and others to work from the Shona culture to find their themes and expression, discovering to his delight that the untrained carvers worked in the same way as Picasso, spending sometimes many days “dreaming” a sculpture complete in detail in three dimensions in the mind and then executing it at great speed.

There was no interest from the white community, though when the workshop began to sell abroad via Lord Delaware, David Stirling and others, it was officially accepted by the museum board. Picasso continued to ask for photographs of the best work: and a trickle of international art experts to the gallery began. The first show of Shona sculpture in London was in 1957.

The National Gallery workshop thrived. There were shows at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1968, at the Musee Rodin in Paris in 1971 and at the ICA in London in 1972, but political tensions in in Rhodesia were such that Frank McEwen resigned in 1973. Thereafter he lived on his boat in the Bahamas (with trips to Brazil, where he had become interested in possible ancient links between South American pre Colombian , and African art) for ten years. Finally he returned to Devon and settled in Illfracombe, not far from his childhood home.

During the 1970’s troubles the Shona sculptors found survival difficult, and the new nation of Zimbabwe, founded in 1980 , had other priorities first. But as fortunes revived a little, the art world began to be shown, and take more notice of, Shona carving (which became broader-based as carvers from other tribes joined the workshops). Worldwide exhibitions became more frequent: film crews began to beat a path to the cottage door of this almost forgotten figure in the late 1980’s; and when 35 tons of stone sculpture were placed at the Yorkshire Sculpture Park in a major exhibition of Zimbabwean stone sculpture in 1990, the exhibition had to be limited to the work of 36 major carvers working in Zimbabwe.

McEwen himself was content to put all this behind him and feed his beloved wild birds as they blew into the cliff-top window of his ex-coast-guard cottage. When pressed, his hope for the future was tinged with his fiery concerns about artistic “quality control” and the dangers of ideological suppression of the world of spirit which sustains African art.

McEwen was appointed OBE in 1963. He is survived by his wife Ann, and a son (Francis Wood McEwen Aldridge) from a previous marriage.

© copyright 2007 Adele Aldridge, all rights reserved.

_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)